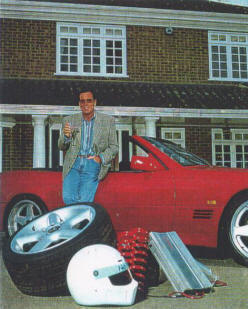

| Not a lot of people know him No8. Keith Ripp He’s helped more boy racers go faster than any other tuning specialist. James May meets the Godfather of bolt-on goodies.  Pulling into the drive, I am confronted by a gleaming

testimonial to the man I am about to meet: a bright red SL, parked

at a rather cocky angle with its wheels turned slightly away,

brochure-style. A beautiful car by anyone's standards, but even so,

my latest subject has chosen to make a few alterations. There's a

bit of bodykit, a definitely non-standard steering wheel and some

very tasty alloys. 'It's only the 300, but it has been chipped,'

he admits, sheepishly. But then he is Keith Ripp, founder of

Ripspeed, the go-faster guru. Pulling into the drive, I am confronted by a gleaming

testimonial to the man I am about to meet: a bright red SL, parked

at a rather cocky angle with its wheels turned slightly away,

brochure-style. A beautiful car by anyone's standards, but even so,

my latest subject has chosen to make a few alterations. There's a

bit of bodykit, a definitely non-standard steering wheel and some

very tasty alloys. 'It's only the 300, but it has been chipped,'

he admits, sheepishly. But then he is Keith Ripp, founder of

Ripspeed, the go-faster guru.A tasteful job, this Merc, but even so, it lent weight to my suspicion that the man who can squeeze more wheel under a wheel-arch than any manufacturer intended must be, well, a bit of a wide boy, surely? I found him relaxed in jeans and check shirt, wearing a little bit of gold (bodykit?) and looking suspiciously bronzed for an Englishman emerging from winter; but there was no hint of furry seat cover or dangly football boots about the man. Even after 24 years, he still seemed mildly surprised by the success of the whole thing. And it is surprising. For Ripp, a man quite happy to flout the intentions of the world's great car designers, is no engineer. 'I never manufactured anything, and I've never built an engine myself, though I've always been able to talk my way through it,' he admits. Rather, his skill has been in anticipating trends and sourcing bits and pieces: he came up with sill extensions and alloy wheels long before car maker’s thought of them and neatly anticipated the car hi-fi boom. 'But I was never even trained as a mechanic - I was a sausage salesman.' >We need to go back to school in Enfield, London, where Ripp (no surprise on this page) was no bloody good and 'got six of the stick probably twice a week' - bear in mind that he was only there for half of it. He was thrown out at 15 with no qualifications and harbouring only one ambition: to own a shop, as his father did. After failing to qualify as an electrician and the lengthy stint with the sausages ('I was my own guv'nor - that was my training') he found, in his early twenties, the inspiration for his retail endeavours. This was the Rallycross era, and Ripp had become a keen Mini racer. But he found it difficult to get hold of the race parts he wanted, so 'I decided to open a store instead of buying a house.' With a total budget of £750 he was lamentably short of stock for his Mini-tuning business: 'Every weekend I would strip down my racing car and put all the body parts in the window, to make it look prettier.' To maintain the illusion, 'I'd sell a part, take it out of the box, give it to the customer and put the empty box back on the shelf.' Even so, the venture was an immediate success with the thousands of Mini-racing enthusiasts from around the world who shared the problem of parts availability. A lack of stock had given way to a lack of space, so Ripp moved five miles down the road to Edmonton, where he bought three adjoining shops and knocked them through to form one. He also opened two more branches in Pinner and Luton. 'On Saturday, they'd be queuing up outside the door, waiting for it to open.' Space again became a problem, and the will to move came from 'about a ton' of parts that crashed through two floors from the attic. This time, he closed all his other branches and opened a purpose-built superstore for the parts that now bore his name. By now he had largely abandoned tuning parts for Minis, seeing no future for the car ('That was a mistake; this was just before they relaunched the Cooper') and instead concentrated on the 'bolt-on go-faster goodies.' Wheels and exhausts added to the success enjoyed by body mods; soon after, Ripp was in at the beginning of the hi-fi explosion. 'The superstore was a new idea in 1981, and everyone in the industry said it wouldn't work,' he recalls with a smirk. It is, of course, still there. But it is no longer his. Two years ago Ripp sold the whole business: 'I thought I'd taken the company as far as I could on my own. And I was burnt out. I needed time off.' He was also ill. A series of ailments were diagnosed as the result of work-related stress. 'I sold the company, got rid of the stress, but still had the aches.' Further consultation revealed a heart condition requiring a triple-bypass operation.  It

would be distasteful to say that this was the body modification to

end all body modifications, except that Ripp is in such

overwhelmingly rude health. At 49, he could quite obviously retire

to the comfort of his huge house, but he's looking restless. 'I have

a vision of the future for the car accessories industry,' he says

mysteriously; more importantly, he has a son 'ready to do the real

work for me.' The numberplate on the SL reads RIP, but don't bank on

it. It

would be distasteful to say that this was the body modification to

end all body modifications, except that Ripp is in such

overwhelmingly rude health. At 49, he could quite obviously retire

to the comfort of his huge house, but he's looking restless. 'I have

a vision of the future for the car accessories industry,' he says

mysteriously; more importantly, he has a son 'ready to do the real

work for me.' The numberplate on the SL reads RIP, but don't bank on

it.Copyright June 1996, Emap. Author: James May |